Black Bottom: The Road between the Past and the Future

Black Bottom and Paradise Valley; a forgotten metropolis, lost to Detroit through the constant industrialization and the enthusiasm for urban renewal that led to the destruction of a cultural and economic epicenter, on par with the likes of New York City’s Harlem and New Orleans’s Bourbon Street. Now, Black Bottom only exists in our hearts and spirits of those who hold fond memories of the demolished neighborhood. While studying various aspects of the city It absolutely baffles me how phenomena like Black Bottom were not to be found anywhere in my history textbooks as a child, or even recounted to me by my mother and grandmother, who are both life-long residents of Detroit. This led to an almost comical pursuit of every Detroiter I knew who would have some recollection of Black Bottom or would at least recognize the name of Detroit’s famed lost neighborhood, almost bearing likeness to the myth of Atlantis; however, there is tangible proof that Black Bottom once existed, whether people’s memories reinforce that claim or not, is an entirely different story. Usually when coming across unfamiliar historical topics, the best primary source to pursue is my grandmother. She has the uncanny ability to recall almost any historical event, especially those pertaining to Detroit, with absolute clarity. I can remember calling my grandmother, even at a young age, and asking countless questions about her experiences as a Detroiter. Even today, I can make one simple reference to a historical event about Detroit and soon; I’ll be having an hour long conversation about the various injustices that Detroiters—in particular, Black Detroiters—have faced over the years and have continued to face, but even she had no knowledge of the Black Bottom neighborhood. It seemed that certain events such as the Coleman Young Administration, which my mother would like to describe as the best thing that has ever happened to Detroit, and the not-so-recent controversy facing the Kwame Kilpatrick scandal at the Manoogian mansion and the near-simultaneous collapse of the city of Detroit, were within my grasp of understanding, but my discovery of Black Bottom revealed the true ignorance of certain aspects of, both, my culture as an African-American and my hometown of Detroit.

I’m quite sure that if I had never moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania for the duration of most of my teenage years, my interest in historical topics like Black Bottom, would be practically non-existent. But being taking out of your home and placed in an unfamiliar environment, in which, you transition from being a part of the majority—being black in Detroit comes with this privilege—to being almost entirely unrepresented in society, awakens a certain consciousness within you. In South Park, Pennsylvania, which is a suburb of Pittsburgh, I was one of the seven black kids in school. Deprived of my familiar surroundings that I now realize provided me with a sense of comfort that was ripped away when I crossed the Detroit border and somehow ended up in the rural backwoods of Pennsylvania, I felt lost. When my teachers would marvel at the fact that I was intelligent and diligent in my studies, I didn’t realize where that stigma evolved from. I didn’t realize that every time I would be asked if I had been attacked or involved in some gang-related melee, what the implications being made really were. Detroit, my home, had been mocked, scrutinized and vilified as the cesspool of American cities and in the process of the demonizing of the city I should have pride towards and regard with the upmost adoration, I had been left in the rubble with no culture and no defense from the vitriolic words and actions that my peers and mentors had demonstrated. This was not the opinions of just the suburban populace of South Park, this was a pandemic; a reflection of the attitudes that America had towards my hometown.

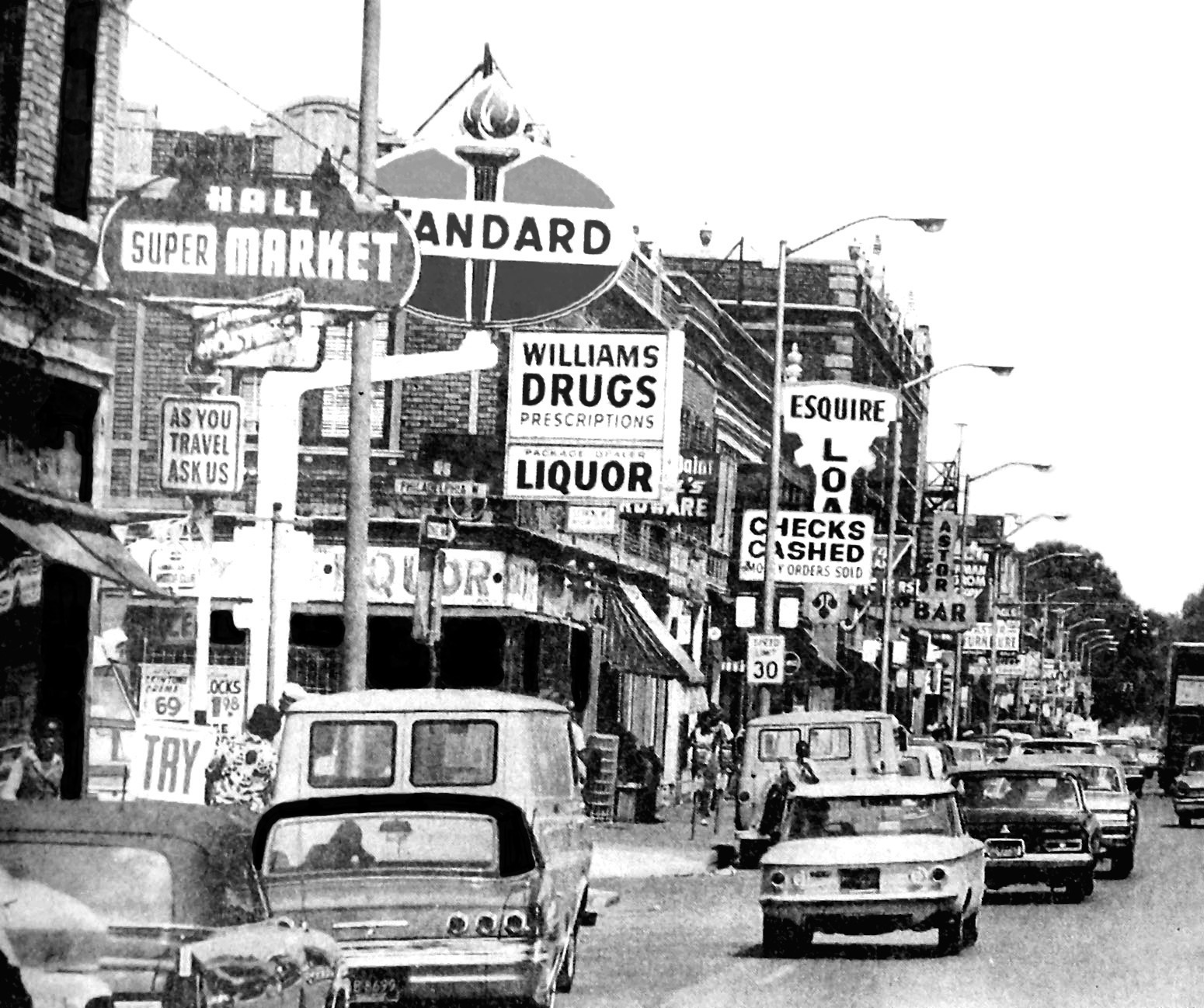

So why did the discovery of the neighborhood of Black Bottom evoke such a strong response within myself? It would be better to first actually define Black Bottom and what it was in relation to Detroit. According to the Encyclopedia of Detroit, found on the website of the Detroit Historical Society, Black Bottom was a predominantly black neighborhood that was located on Detroit’s Near East Side, and it is bordered by Gratiot Avenue, Brush Street, Vernor Highway, and the Grand Trunk railroad tracks, with its main commercial strips being both Hastings Street and St. Antoine Street. While being the cultural center for Eastern European Jewish immigrants prior to World War I, by the 1950s, Hastings Street had undergone a transformation. Resulting from the Great Migration north in search of greater economic opportunities, African-Americans turned Hastings street into one of the city’s major African- American communities, where numerous black-owned enterprises such as hospitals, night clubs and businesses were located and prospered. With the neighborhood becoming a social, cultural and economic hub for the African American community in Detroit, the neighborhood adjacent to Black Bottom, known as Paradise Valley, which bordered Black Bottom on its northern perimeter, became nationally recognized for its contributions to the music scene. Reputable artists such as Duke Ellington, Billy Eckstine, Pearl Bailey, and Ella Fitzgerald regularly performed in the local bars and clubs in the area.

What’s so interesting about this particular area is that this prosperous area that was rich in so many aspects came to be as the result of strict racist and discriminatory housing regulations that did not allow African Americans to be able to move into white neighborhoods. That’s not to say that Black Bottom did not have its problems. According to the Walter P. Reuther Library’s website, under the entry of “Detroit’s Black Bottom and Paradise Valley Neighborhoods”, there is mention that due to an influx of people seeking employment at Henry Ford’s automotive plant after World War II, Detroit faced a serious housing crisis that was only made worse by the racial discrimination that blacks faced back in this time, which resulted in not enough housing to adequately supply the city’s residents. While conditions overall during this time were troublesome, Black Bottom contained the city’s worst and poorest living conditions, in which, many residents found themselves huddled together in a single room with no cooking facilities such as an oven or a kitchen sink and also without any indoor plumbing, resulting in abhorrent unsanitary conditions.

Unsurprisingly, Detroit city government decided during this time to undergo an urban renewal project, now known as I-375 freeway, and Black Bottom was targeted. Using the excuse of the deplorable living conditions of the neighborhood, the city decided to use the neighborhood’s space for the freeway, instead of trying to resolve the crisis. Mentioned in Thomas Sugrue’s book The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, “City officials expected that the eradication of ‘blight’ would increase city tax revenue, revitalize the decaying urban core, and improve the living conditions of the poorest slum dwellers.

Overcrowded, unsanitary, and dilapidated districts like Paradise Valley and the Lower East Side would be replaced by clean, modern, high-rise housing projects, civic institutions and hospitals.” Instead of accomplishing their mission to “improve the living conditions of the poorest slum dwellers”, the resulting effect of the displacement of an entire community people left enterprises completely destroyed and their place taken by a roadway that would only assist the gradual exodus of Detroiters out of the city and into the suburbs and with it, Detroit’s tax revenue and culture. What bothers me in particular about this urban renewal project is that the outcome was of a worse situation than before. According to Sugrue,” the best-informed city officials believed that a majority of families moved to neighborhoods within a mile of the Gratiot site, crowing into an already decaying part of the city, and finding houses scarcely better and often more overcrowded than that which they had left.” The project had been entirely in vain and even worse, the cultural and economic epicenter of Black Detroit had been destroyed and as we see today, it has never truly recovered.

To get back to the initial question of why Black Bottom and Paradise Valley evoke such a strong response within myself; I think that as an African-American who lives in Detroit and has always regarded this city as my home, I feel such a disconnect with history and circumstances like these only worsen that disconnect. Also, looking at current situations in the city, I see a particular trend of history repeating itself. I see multitudes of people in my generation fleeing Detroit at first opportunity and leaving a void of fresh, innovative ideas that could really benefit this city. Another grievance I have is that we see Detroit being discussed only as a dummy project, a prototype for which other, more “successful” cities, can learn from. Haven’t we learned our mistakes from the various urban renewal projects in the past? When will we reflect on ourselves and take into serious consideration that Detroit is a home to people, first, and an urban renewal project in itself, second? I am glad to see Detroit, at least, discussing the possibility of revitalization on an economic level, and being repopulated by numerous ethnic groups, however, we need to be more and more conscious of our previous historical missteps to build a better future and Black Bottom is the perfect example of that. I am doubtful that Detroit will see a resurgence of a neighborhood like that of Black Bottom and that is what pains me the most, but I truly hope that Black Bottom’s erasure will not be in vain and instead will revitalize passion for this city that I feel is currently absent from the youth of Detroit.

Works Cited

"Detroit's Black Bottom and Paradise Valley Neighborhoods." Walter P. Reuther Library. Wayne State University, n.d. Web. 05 Dec. 2015.

"Encyclopedia of Detroit." Black Bottom Neighborhood. Detroit Historical Society, n.d. Web. 1 Dec. 2015.

Sugrue, Thomas J. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1996. Print.

"Urban Renewal and the Destruction of Black Bottom." Environmental History in Detroit. University of Michigan, n.d. Web. 05 Dec. 2015.