Uncovering Calligraphy: Learning the Traditional and Modern Art of Handwriting

Writing originates all the way back to 30,000 years ago in the Paleolithic Era when human beings began making representations of the things around them. As Calderhead and Cohen, editors of The World Encyclopedia of Calligraphy, point out, the first form of “writing” was cave paintings that were discovered in both Southern France and Northern Spain (5). Although these paintings pictures are not necessarily writing in a formal sense, they are markings that express meaning. Actual writing did not emerge until about 3000 BCE in a number of different cultures, such as with the Phoenicians and their set of abstract symbols that represented nothing more than the sounds of speech (Calderhead and Cohen 6). Eventually, writing evolved into complex sets of symbols that represented words of many different languages. As these alphabets evolved and were used over the years, writing eventually became to be viewed as an art form. Calligraphy is a “letter-based art where the quality of gesture is part of the content of the work” (Calderhead and Cohen 4). Because of its importance in the graphic arts, calligraphy is a natural field of study for a graphic designer. The purpose of this directed study was to learn two contrasting calligraphic alphabets; to conduct research on one of the greatest calligraphic masterpieces; and to complete two calligraphic projects that exhibit the insular majuscule alphabet and the italic alphabet. This project has led to an appreciation of the careful work it takes to create such exquisite lettered pieces of art.

Although there has not been a clear definition established for calligraphy because of the crossing of so many different cultures over time, perhaps the best definition for this specific art form is found in Albertine Gaur’s text A History of Calligraphy, which states that calligraphy is a “harmony between script, tools, text and cultural heritage” (3). The term “calligraphy” derives from the Greek words καλλι (kallos) and γραφειυ (graphein), which translate to English as “beautiful” and “to write” (Calderhead and Cohen 4). Therefore, in order for text to be known as calligraphy, it must be striking to look at. However, not just any beautiful handwriting can be labeled as calligraphy. There are a number of elements that must be united in order for true calligraphy to develop. These elements are the availability of tools, motivation, and the existence of certain rules which “guide the construction of letters and the relationship between line and space” (Gaur 143). If all these elements are kept in mind while writing, “beautiful writing” can eventually make its way towards true authentic calligraphy.

The first necessary steps taken in this calligraphic study were to learn more about the tools needed in order to practice calligraphic handwriting. The first tool needed, of course, is the pen. The edged pen is essential for calligraphic practice because of its unique square-cut tip. This tip creates thin or thick marks while writing, depending on the direction of the strokes made. Though many calligraphers throughout history used reed (introduced by the Greeks in 3rd century BC) and feathers (in 6th century AD) for pens, the most popular and desired material for a pen is metal (Gaur 24). The metal pen was created some time in the mid-18th century along with the rapid increase of businesses, administrations, and schools in Western Europe. France, Germany, the United States, and England have all claimed to be the first countries to make the metal pen, but no documentation has officially confirmed which country is its birthplace (Gaur 29). Metal edged pens were found to be more durable and simpler, and they did not need to be constantly recut or reshaped like the former reed pens and quills. Nowadays, metal pens are also designed to allow different nibs varying in size to be detached and replaced, giving calligraphers another way to create thinner or thicker marks instead of solely focusing on the direction of strokes they make (Gourdie 3).

Another utensil needed for the art of calligraphy is the ink. Up until the mid-19th century, the two basic types of ink used for writing were carbon inks and iron-gall inks (Gaur 34). Though carbon inks continued to be used along with iron-gall inks in medieval manuscripts up to the 12th century, iron-gall inks were made to be a better medium in the Middle East (Gaur 34). This type of ink is made from oak galls – growths found on leaves, bark, stems, and even acorns and roots – that produce a purple-black or brown-black ink. Iron-gall inks can fade over time and consume the paper, causing a lot damage to the piece, but iron inks are not easily erased. No matter which type of ink was used, medieval scribes used a variety of colored inks. Red was the most substantial color used, helping to bring importance to headings, titles, initials, rubrics, or for marking specific dates in calendars (Gaur 34). Ink is used either by dipping a pen in a bottle of ink or, nowadays, by using replaceable ink cartridges that can be placed inside a pen. The favorite inks listed by Laura Lavender, one of the authors of Creative Lettering and Beyond, are sumi, walnut, and – the seemingly more popular kind of ink – acrylic (9).There is no specific type of ink that is recommended today for the art of calligraphy since there are so many different kinds. It is most commonly recommended, however, to use black non-waterproof ink because it tends to have the best texture (Kirkendall et al. 9). Colored inks and fountain pen inks are generally not used, as these are thin and often do not create an even, opaque stroke (Calderhead and Cohen 30). Lastly, paper is needed for calligraphic practice. For many years, papyrus – a thick paper-like material made from the fibers of the papyrus plant – was the sole material for calligraphers to write on. Parchment, which is a writing material prepared from the skin of an animal, increased in popularity after 300 AD (Gaur 34). For today’s needs in calligraphy, the paper used should not be highly absorbent since this will not produce the crisp, sharp edges that are so essential for when writing with ink. To avoid fibers of the paper from getting caught in the nib of the pen, it is recommended to use smooth paper (Kirkendall et al. 9). In fact, many calligraphers will use paper that is designed for print-making (Calderhead and Cohen 30). After learning about all the necessary tools’ importance in calligraphy, it was deemed necessary to conduct research on the artful alphabet that was so common when calligraphy was first practiced.

Insular majuscule became the ideal style of writing between the 4th and 8th centuries (Calderhead and Cohen 41). It is a transitional form of writing as it mixes letters that would later develop into today’s minuscules with letters directly based on Roman capitals (Calderhead and Cohen 41). It found its highest appearance in the famous manuscript, the Book of Kells. With the magnificent calligraphy of the Book of Kells set as an inspiration, calligraphic practice on the insular majuscule alphabet began. Although instructions found in The World Encyclopedia of Calligraphy were helpful during practice, The Puffin Book of Lettering by Tom Gourdie was preferable as a guide to learning the insular majuscule alphabet. While viewing the alphabet displayed on the book’s pages, practice was done in an ordinary notebook. Insular majuscule is based on the circle, having curved and rounded letters. Writings in Insular majuscule exhibit a “rhythm of curves and straight upright strokes in a stately progression across the page” (Calderhead and Cohen 41). When writing, the pen should be pointed towards the body. This helps vertical strokes to go on the paper heavily while horizontal strokes come out light.

Study of early calligraphic techniques led to the study of the most famous example of the early manuscripts, the Book of Kells. A 13th century historian named Giraldus Cambrensis once described this book as “the work, not of men, but of angels” (qtd. in Meehan, Book of Kells 9). The Book of Kells is a large-format (13 inches by 10 inches) manuscript of the four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) written in Latin (“The Book of Kells”). Instead of ordinary paper produced from the pulp of plants, the pages of this Book were made of vellum, which is a parchment made from calf skin. Though it is believed to have been created in 800 AD, the Book of Kells’ place of origin remains controversial. This is most likely because of its relocation from Iona – a small island off the western coast of Scotland – to Kells – a town located about forty miles north of Dublin – during a series of Viking raids in the year of 807 (Meehan, Book of Kells 10). The monastery in Iona that is argued to be the birthplace of the Book of Kells was founded by St. Colum Cille, the monk to whom the Book is traditionally attributed. The monastery in Kells is known to have been the house of refuge for the Book for when the Viking raids took place. As for the purpose of its creation, the Book of Kells is “the medium which conveyed the fundamental message of Christianity” (Meehan, Book of Kells 32). It is believed to have been created for use in the church on special occasions, such as on Easter, rather than for daily services ("The Book of Kells"). The manuscript was constructed so that it was large enough to be visible to a sitting congregation in the front of the church, even though it was believed that only the spiritual elite would be able to interpret the true meaning of the text and ornamental symbols (Meehan, Book of Kells 30).

Before and during the time of the Book’s creation, specifically from the late 600s to early 800s, manuscripts were created to high artistic standard (Meehan, Treasures of Ireland 48). The artistic style of writing at this time was Insular Majuscule, an upper-cased medieval script system often used in monasteries. Commonly in these ancient manuscripts, including the Book of Kells, significant words or phrases were emphasized with red dots around the shapes of the letters for purposes of highlighting (Meehan, Book of Kells 17). The text throughout the Book is also often decorated with symbols of great importance, commonly featuring plants, animals, and people ("The Book of Kells"). These motifs have figurative, symbolic, and ornamental significance (Meehan, Book of Kells 18). Most of these designs express great meaning in relationship to Christ, the subject of the four Gospels. An example of an ornament widely used throughout Kells as a symbol of Christ is the snake, which represents his resurrection (Meehan, Book of Kells 17-18). Another common type of décor was the embellished initial letters of verses that formed parts of the text. Overall, décor helped “[punctuate] text and [aid] legibility” (Meehan, Book of Kells 29). Highly decorated pages are scattered throughout the Book as well. These pages include canon tables, which are concordances of Gospel passages to two or more of the evangelists, and carpet pages, pages typically placed at the beginning of each Gospel containing artistic patterns and symbols. These carpet pages usually were unrelated to the text, and usually included the cross (Meehan, Treasures of Ireland 50). The decorative pages that introduced each Gospel included a page of evangelistic symbols (the Man, the Lion, the Calf, or the Eagle to represent Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John respectively), a portrait page, and an embellishment of the opening words of the Gospel (Meehan, The Book of Kells 22). The most famous decorative page of the entire Book of Kells, and of medieval calligraphic art overall, is the Chi Rho page (folio 34r) (“The Book of Kells”). This page presents the nativity based on Matthew’s depiction of the event and the renowned symbol, which consists of the first two letters of the Greek word for Christ (“ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ”). The Chi Rho motif expresses the same meaning as the cross does, symbolizing Jesus as the Christ. In the Middle Ages, a specific alphabet naturally began to take form, incorporating all the various languages in the region of Western Europe. This alphabet became known as the Roman alphabet. This specific script can be traced back to the Phoenician consonant script, which first appeared in Italian inscriptions dating back to the 6th or 7th centuries BCE, and which flourished between the 13th and 3rd centuries BCE (Gaur 47). However, it was not until the Middle Ages when the Roman alphabet began to unite all the different languages of the region, making it the basis of modern Western calligraphy. There are the familiar 26 individual lettered symbols in the Roman alphabet, which can be written in both directions – left to right or right to left, depending on the language being used. Colonization and commerce has continued the spread of the Roman alphabet since the 19th century. Deriving from this alphabet, a specific script came about that was chosen as an introduction to the practicing portion of this project.

The Italic alphabet originates from Italy during the time of the Renaissance. This script was used both as a formal style of text and as the basis for day-to-day handwriting. This style is based on the oval, and the letters are compressed and require more strokes (Gourdie 28). Being one of the most popular and common scripts in history, it seemed obvious to use this style of writing to ease the transition from ordinary handwriting to the correct ways of writing artfully.

The resources that became very helpful in the initial practice of writing in Italic were the Italic Handwriting Series workbooks, specifically volumes D and E, published by Barbara Getty and Inga Dubay of Portland State University. These books were used regularly over the semester to aid the introduction to calligraphic writing. While practicing, specific vocabulary concerned with the make-up of letters was acquired. These terms include ones like “bowl” (the round outer part of a letter), “hairline” (the thinnest stroke found in a specific script), “ascender” (portion of a miniscule letter that extends above the baseline of a font), “descender” (portion of a miniscule letter that extends below the baseline of a font), and much more ("Type Glossary"; King). As practice progressed, techniques of proper writing were discovered. Firstly, it is very important to point the nib of the pen onto the paper in the correct angle, precisely 45 degrees in the case of writing in Italic (Gourdie 18). The position in which the pen is held, as well as the speed of writing, affects the flow of the ink, creating thinner or thicker strokes. Pulled strokes – never pushed – should typically use the full width of the nib’s edge, creating thick lines. Strokes made in a diagonal direction to the edge of the pen form a medium thickness. Curved strokes create lines that wave from thick to thin or thin to thick, and back again, as the pen shapes an arc (Calderhead and Cohen 17). Strokes written horizontally form thin lines.

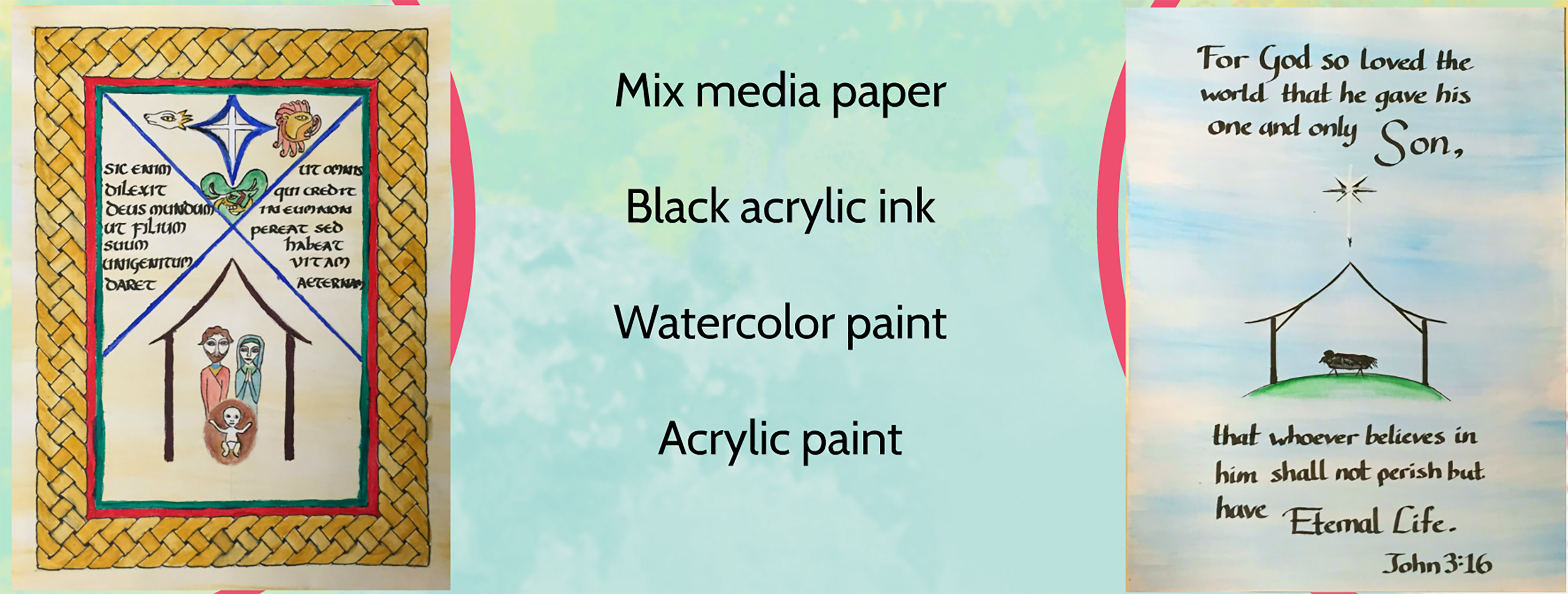

Two works were created next to exhibit what had been learned throughout this directed study. Since the presentation for it would take place so close to the holidays, it seemed convenient to pick a theme that related to Christmas. The verse chosen to be illustrated in these projects was John 3:16 – “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” The first piece was done in an insular design, which included the insular majuscule alphabet, and illustrations and décor that were inspired by the Book of Kells. The second project was finished in a modern design, which included the italic alphabet and was inspired by contemporary pieces often viewed through social mediums of the Internet, especially Tumblr. The informative and instructional book Creative Lettering and Beyond by Gabri Joy Kirkendall, Laura Lavender, Julie Manwaring, and Shauna Lynn Panczyszyn was also influential in the modern design project. The similarities and differences between the alphabets were reinforced through the crafting of these two uniquely related pieces.

Because of the inspiration gained from the Book of Kells, the insular project is written in the insular majuscule script, mimicking the rounded and ancient style of text found in the Book. The verse is also written in Latin in order to stay true to the Book of Kells. It is also decorative, similar to how the Book’s carpet pages are ornamental. An embellishment included in this project is the Celtic border, which is a design that was developed in Ireland, as well as other countries in the region, that commonly reoccur in medieval manuscripts like the Book of Kells. The instructional YouTube video titled “Celtic Knot - 2” was especially useful in creating this décor. Symbols like the cross, the lamb, the lion, and the snake, and images of the nativity scene and the Star of Bethlehem were all included to bring more prominence to the meaning of the verse John 3:16.

The Italic alphabet was used for the modern design project because of its popularity and familiarity nowadays. This project was created to be simpler in order to adhere to the more contemporary style of calligraphic art. Though this modern design lacks a little in décor, it still includes the essential nativity scene and Star, though in a more minimalistic fashion. The media in which these projects were made are very similar. The insular design was created on smooth mix media paper, which is intended for the use of watercolor and acrylic paints, and pen/pencil. This was perfect because black acrylic ink was used for writing the Insular majuscule script and various colored watercolor and acrylic paints – specifically red, green, yellow, and blue pigments because of their relevance in the Book of Kells – were used for the ornamental values throughout the rest of the page. The modern design was created identically, using the same mix media paper, black acrylic ink for the text, and minimal colored watercolor and acrylic paints for the pigments throughout the piece. Overall, these two projects differ in the style of their scripts and ornamental designs, and are similar in their methods of creation, but they both still convey the same message – the wondrous story of Christ’s birth.

Throughout this directed study, I have learned much about calligraphy through research on the subject matter, through writing practice, and through the completion of two calligraphic projects to exhibit two specific styles of writing – the insular majuscule alphabet and the Italic alphabet. I feel as though I have gained a lot from this directed study. Although I only started out practicing with the simple Italic alphabet, my first hand at calligraphy can be described as very difficult. Transitioning from my typical note-taking ballpoint pen to a metal edged cartridge/dipping pen, and transitioning from the comfort of the awkward way I normally hold my pen to the correct way of holding a pen – it was a challenging introduction to the art form. However, I became a fast learner and improved in my practice of the art of calligraphy, moving from the italic alphabet to the insular majuscule alphabet within the first half of this study. Although I enjoy both the italic and insular majuscule alphabets, I prefer the insular majuscule script. Italic is easier to work with, but insular majuscule is much more artistically appealing to me because of its uniqueness. I enjoyed working on the insular project more out of the two designs I completed for this study. It was delightful to be able to find inspiration from the Book of Kells and create my own insular majuscule-based project. It was gratifying to be able to exhibit my drawing and design skills as well. Both projects granted me a lot of creative freedom, especially the modern design. Overall, I have learned much about the significance and importance of calligraphy. Over the course of this entire study, I have developed a great appreciation for this art because of the hard work and patience it takes to create something so vast and beautiful. Although some people may believe this art form may not be suitable for everybody, I believe anyone is capable of becoming a talented calligrapher if one is diligent. Its benefits are certainly immeasurable. Albertine Gaur mentions this in her book A History of Calligraphy: “Writing informs us about content in a verbal manner, calligraphy communicates something beyond the mere verbal” (145). No matter which style, alphabet, or script is used – traditional or modern – calligraphy conveys meaning. Calligraphy delivers a message. Calligraphy expresses art. And all of this is done with just a pen, ink, paper, and a persistent and creative mind.

Works Cited

"The Book of Kells." The Library of Trinity College Dublin. The University of Dublin, 22 June 2015. Web. 08 Oct. 2015.

Calderhead, Christopher, and Holly Cohen. The World Encyclopedia of Calligraphy: The Ultimate Compendium on the Art of Fine Writing. New York, NY: Sterling, 2011. Print.

"Celtic Knot - 2." YouTube. YouTube, 04 Nov. 2007. Web. 10 Oct. 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_O_0yegDdIw. Gaur, Albertine. A History of Calligraphy. New York: Cross River, 1994. Print.

Getty, Barbara and Inga Dubay. Italic Handwriting Series. Vol. D: Basic & Cursive. Portland, OR: Continuing Education Press, Portland State University, 1994. Print.

---. Italic Handwriting Series. Vol. E: Basic & Cursive. Portland, OR: Continuing Education Press, Portland State University, 1994. Print. Gourdie, Tom. The Puffin Book of Lettering. New York, NY: Penguin, 1961. Print.

King, Don. "Glossary: A Compendium of Calligraphic Hands & Terminology." Triangle Calligraphers' Guild. Triangle Calligraphers' Guild, 2015. Web. 14 Sept. 2015.

Kirkendall, Gabri Joy, Laura Lavender, Julie Manwaring, and Shauna Lynn Panczyszyn. Creative Lettering and Beyond. Irvine, CA: Quarto Group USA, 2014. Print.

Meehan. Bernard. "Irish Manuscripts in the Early Middle Ages." Treasures of Ireland. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1983. 48-57. Print.

---, Bernard. The Book of Kells: An Illustrated Introduction to the Manuscript in Trinity College, Dublin (Second Edition). London: Thames and Hudson, 1995. Print.

---, Bernard. The Book of Kells. London: Thames and Hudson, 2012. Print. "Type Glossary." Typography Deconstructed. Typography Deconstructed, 2010. Web. 15 Sept. 2015.