The Lost Generation and Millennials

ABSTRACT - There is much to be learned about today’s society by studying the works of the past. This paper will compare the situations and issues of “the lost generation” of the 1920s to the “millennials” of the early 2000s, showing that despite the large difference in time, the two generations are facing common problems. The term “lost generation”, coined by Gertrude Stein, is applied to a group of writers, poets, and musicians in Paris during the 1920s, often characterized by the similar themes discussed in their work, such as disillusionment in the post-World War I society, loss of identity and tradition, and an uncertainty of the future. Research was completed on the lost generation through academic publications along with the works of lost generation authors such as Gertrude Stein, Sylvia Beach, Ezra Pound, T.S. Elliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway. The term “millennials,” coined by Neil Howe and William Strauss, describes those born during the turn of the millennium. These young adults are often stereotyped as lazy, self-obsessed, and entitled which explains why they often reject the term millennial, viewing it as derogatory. Research on millennials was completed through books, articles in periodicals as well as studies from the Pew Research Center. There are many similarities to be found between the two generations, starting with the circumstances of their youth. Both the 1900s and the 2000s were a period of wartime followed by an economic depression. These events alter lives, as shown by one of the topics the lost generation chose to write about. A lack of tradition, particularly religion, an increase of substance abuse, and the desire to travel are displayed in both generations as well. However, the most important thing that connects the two generations is optimism. The lost generation, particularly Ernest Hemingway, did not accept that he was lost. Many millennials have the same thoughts as Hemingway, believing that while their current situation may not be ideal, that their future will be.

The Lost Generation and Millennials

This paper shall discuss “the lost generation,” including their history and common themes found in their work, and compare their experiences to what “millennials” are facing. The analysis of the lost generation will be completed by providing historical background on the lost generation followed by a literary analysis of various lost generation writings. The comparison will begin with the origin of the term millennials proceeded by why the lost generation and millennials are similar.

The beginning of the 1900s was a tumultuous time for America. The turn of the century was influenced by an increase in industrialization, social and cultural shifts, and rapid economic changes. However, it was World War I that left the largest impact on society, due to its unrivaled amount of carnage and destruction. Trench warfare along with the introduction of modern weaponry caused the deaths of more than 9 million soldiers along with leaving more than 21 million wounded (“World War 1”). The men lucky enough to survive had to deal with the horrors of what they witnessed along with the deaths of their comrades. Some Americans chose to leave the country after the war, either seeking a culture richer than young America’s or escaping the increase of puritanism and commercialism, becoming expatriates (Earnest vii). One group of authors, poets, artists, and musicians chose specifically to move to Paris in the 1920s, later becoming known as “the lost generation.”

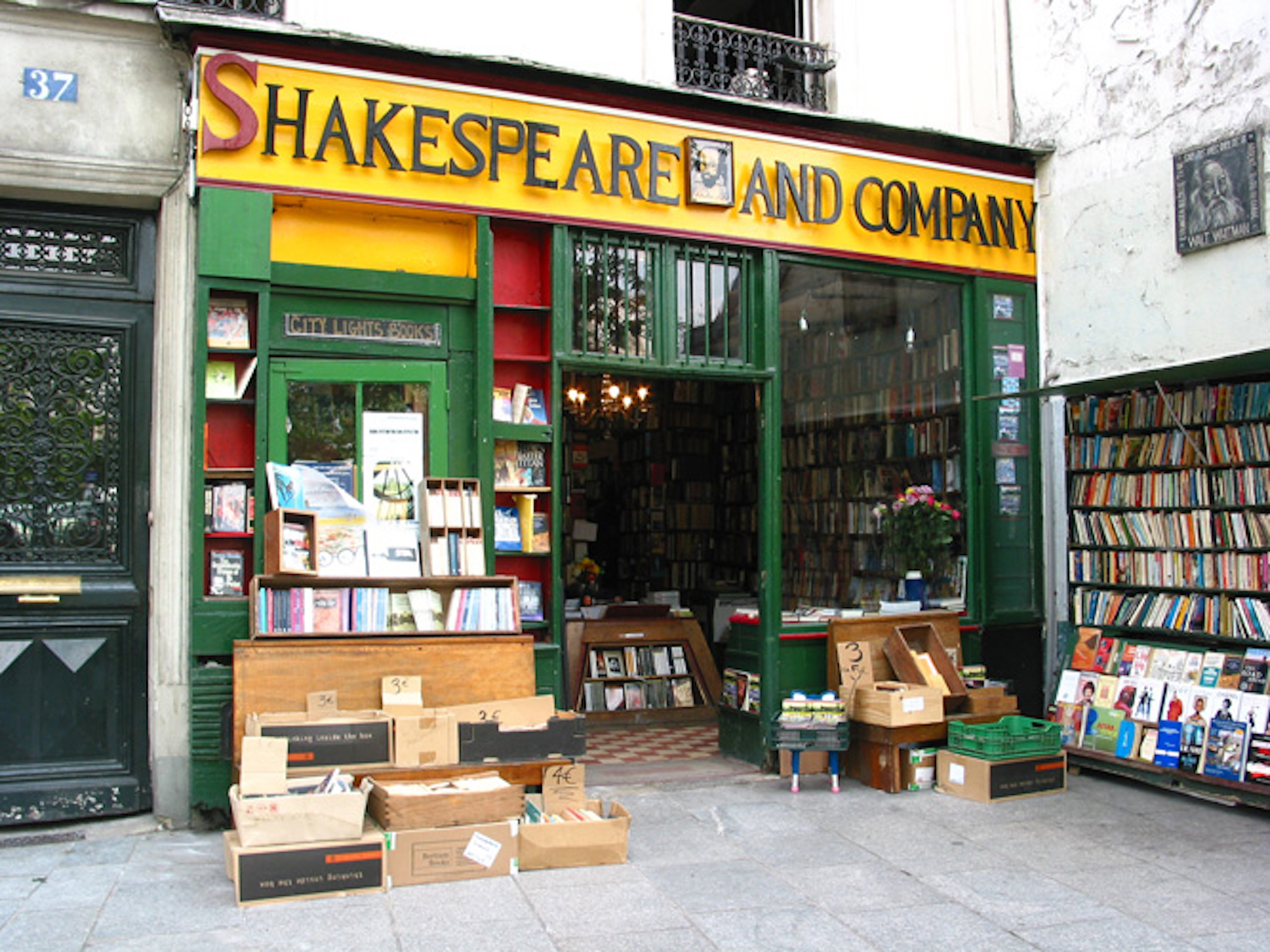

According to Ernest Hemingway, it was Gertrude Stein who first coined the phrase “lost generation.” In his memoir A Moveable Feast he tells the story of Stein taking her Model T to a mechanic who did not fix her car to her liking. She remarks “That’s what you all are…All of you young people who served in the war. You are all a lost generation” (Hemingway, A Moveable Feast 34). Described as a “very big but not tall” woman with “beautiful eyes” (21), Stein was quite fond of the lost generation and frequently invited the members to her literary salon. Located in her apartment at the famous 21 rue de Fleurus, the salon featured Cézanne oils and watercolors, early pictures by Matisse, paintings by Braque, Renoir, Manet, Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec, and original Picasso sketches (Mellow). It is in this salon that writers such as Ernest Hemingway sought out Stein’s thoughts on literature and their own work; Stein is often referred to as the mother of the lost generation writers. Another famous location associated with the lost generation is Sylvia Beach’s bookstore Shakespeare and Company. Beach opened the bookstore on November 17, 1919 (Fitch).

Hemingway described the store as a “warm, cheerful place with a big stove in the winter, tables and shelves of books, new books in the window, and photographs on the wall of famous writers both dead and living” (Hemingway, A Moveable Feast 39). Shakespeare and Company made an impression on the French, particularly the writers and artists, because never before had there been an English-language bookstore and lending library in Paris. Beach attracted names such as Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Robert McAlmon, and John Dos Passos, among others (Beach 109-112). Sylvia Beach helped shape the lost generation, as her bookstore provided access to current American literature for reading and criticism along with support for young authors, whether it was lending them money, finding them resources, or simply encouraging them to write. The lost generation writers flocked to places such as Shakespeare and Company and literary salons to surround themselves with like-minded individuals. These writers were shaped by the shared experience of World War I, often choosing to express their feelings about the war and the post-war society through writing. Young men craving adventure and travel enlisted in World War I, but found that instead of a rewarding experience, war was filled with violence and death. The lost generation then felt the need to travel, not for adventure, but as a way to deal with the post-war society. Hemingway himself made this choice, signing up for active duty after witnessing the war as a reporter, and drove an ambulance along with fighting on the front lines. After less than a month in the war zone, Hemingway was struck by a mortar shell and severely wounded (Wagner-Martin 23). In Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, the main character, Jake, is dealing with his physical and emotional wounds after World War I. Jake travels to Spain frequently to fish and witness the bull-fights. At first, Spain is everything Jake needs, as he is free to watch the bull-fights and fish, but the charm quickly wears off. “I hated to leave France. Life was so simple in France. I felt I was a fool to be going back into Spain. In Spain you could not tell about anything” (Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises 233). Expatriates believed that by moving to Paris, their troubles would be cured, but that was not true.

Along with travelling to physically escape, the lost generation was known for drinking as a mental escape. The theme of alcohol is apparent in The Sun Also Rises along with Hemingway’s memoir A Moveable Feast, mentioning alcohol at almost every social gathering. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby also refers to alcohol and decadence as a coping tool. Jay Gatsby, one of the main characters of the novel, throws luxurious parties full of dancing and drinking that last all night in an attempt to gain the attention of his lost lover, Daisy, who refused to marry Gatsby because he lacked wealth and stature. Gatsby finally meets up with Daisy and attempts to win her back by showing off his large mansion along with his expensive belongings, and Daisy agrees to leave her husband and run away with Gatsby. It is alcohol that plays a part in the book’s tragic ending, though, as the drunk Daisy driving Gatsby’s car with Gatsby in the passenger seat, hits and kills another character, Myrtle. Wilson, Myrtle’s husband, kills Gatsby in his grief, blaming him for his wife’s death, relaying Fitzgerald’s message that excessive materialism and drinking will cause destruction. In another Fitzgerald novel, Tender is the Night, the character Abe represents loss of youth due to alcohol. Abe is a raging alcoholic, but fondly thinks back on when he did not face his addiction. Ultimately, Abe’s drinking leads to his demise, as he is beaten to death in a speakeasy (Fitzgerald, Tender Is the Night), another Fitzgerald character killed due to alcohol.

T. S. Elliot, one of the most famous poets of all time, also wrote about lost youth in his poem The Wasteland. The poem begins with the lines:

April is the cruelest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land,

mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Elliot’s lines suggest that April, usually a time of new beginnings and hope, does not provide relief, instead reminding of the painful memories of war. The “dead land” can be interpreted literarily, as the war left millions of dead bodies lying on the battleground, many young men who once had promising futures. Instead, it was winter that provided relief, because it covered up the memories, suggesting that it was easier to be numb. Elliot may have been referring to shellshock, a condition where war survivors found themselves in a state of numbness and disbelief as a way of handling their memories. Living in a state of perpetual shock makes it more difficult to move on and find happiness, adding to the lost generation’s loss of innocence. Ezra Pound, a famous lost generation poet, also wrote about lost youth in his poem And the days are not full enough. It reads:

And the days are not full enough

And the nights are not full enough

And life slips by like a field mouse

Not shaking the grass

Pound’s poem speaks to how lost the lost generation was. Many of the members lost their youth and innocence in World War I and sought to regain it but could not. They wandered and travelled, never truly fitting in and finding satisfaction. In Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, the narrator remarks on the state of events, saying, “I see now that this has been a story of the West, after all-Tom and Gatsby, Daisy and Jordan and I, were all Westerners, and perhaps we possessed some deficiency in common which made us subtly unadaptable to European life” (Earnest 272). Another Fitzgerald novel, This Side of Paradise, features Amory Blaine, a main character who travels Europe with his mother and when he returns to America finds that he cannot relate to the other children (Fitzgerald, This Side of Paradise). This is another example of a lost generation writer speaking about the loss of youth and the inability to regain it. Along with a loss of innocence, The Wasteland spoke to the loss of civilized culture. Elliot includes obscure, incomplete allusions to classic literature to represent how the younger generation was forgetting their traditional values (Shmoop Editorial Team). After the destruction of World War I, many expatriates did not recognize the society they once lived in, driving them to find a new one. The increase in technology that once seemed hopeful was used for violence during the war; the economic prosperity the country was now facing seemed to have been bought with soldier’s lives. Traditions that once seemed important no longer held any value. The 1920s was a period of change, particularly for women. Gender roles began to shift as many women asserted their new independence after earning the right to vote by choosing to cut their hair short, wore shorter and tighter dresses, drank, and smoke. The idea of a masculine woman began to appear in lost generation works, such as Brett Ashely in The Sun Also Rises and Jordan Baker in The Great Gatsby. Brett wears her hair short and holds her own with the multiple men in her life, maintaining several romantic relationships throughout the novel. Jordan Baker also wears her hair short and is a professional golfer and earns her own living, travelling the country. Tom Buchanan, a traditional masculine character, remarks that Jordan’s family “oughtn’t to let her run around the country this way” (Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby 24). Tom Buchanan did not fight in World War I, meaning he was not exposed to the violence of trench warfare where men were forced to huddle together for long periods of time. In The Sun Also Rises, Jake is castrated due to a war injury, a very literal symbol for the loss of masculinity. (Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises). He is subservient to Brett, responding to her every call, despite her being with other men. The other men in the novel are also dedicated to Brett, often taking out their insecurities on one another. The loss of traditional gender roles is just another issue the lost generation dealt with after World War I.

The nicknames for generations did not stop with the “lost generation,” as they were followed by “silent generation,” to “baby boomers,” to “Generation X,” to now, “millennials.” Millennials refer to young adults born between 1980 and the mid-2000s (Advisors). They are often characterized by their narcissism and sense of entitlement, nicknamed the “Me Me Me Generation” (Stein). These stereotypes do not always hold weight, though. Older generations who did not grow up with social media platforms may not understand the millennials desire to publicize their lives, calling it self-obsession. Millennials are the most educated generation of Americans so far, as 61% have attended college compared to 45% in previous generations (Advisors). What may be interpreted as self-entitlement may actually be a millennial seeking a work path that matches their educational experience.

Despite being a hundred years apart, millennials and the lost generation have commonalities due to similar experiences and hardships. The lost generation was greatly affected by World War I, while millennials have grown up during the War on Terror. After 9/11 the United States sent troops into Afghanistan. Over a 10 year period, the War on Terror has expanded globally, uncovering new enemies, most recently the terrorist group ISIS. Growing up in a period of war has left both generations disillusioned from society, with nearly 64% of millennials believing that you cannot be trusting when dealing with people (Kohut, Taylor and Keeter 113). Both generations have also experienced periods of economic prosperity followed by depressions: the lost generation faced The Great Depression, while millennials faced The Great Recession, the worst economic period since The Great Depression (Domitrovic). During this time period, unemployment was at its highest from 2007 to 2009, leaving millennials struggling to find jobs in the competitive labor market (Advisors). A college degree was a necessity for a job, but college costs were higher than ever, with student loan debt nearly quadrupling over the past decade (Raphelson). However, as more millennials went to college, the value of their degrees has decreased, leaving millennials still searching for jobs. The implications of facing The Great Recession during childhood and young adulthood have large and lasting impacts on lifetime wages, particularly for college graduates. “Research shows that entering the labor market during a recession can result in substantial earnings losses that persist for more than a decade, with negative effects lasting longer for college graduates. 40 workers who start their careers in a recession earn 2.5 to 9 percent less per year than those who do not for at least 15 years after starting a career. Research further suggests that one reason for these lower earnings is that new entrants take jobs that are a worse fit for them when they start their careers in a recession” (Advisors). Growing up during a period of wartime along with economic depression has caused millennials to lose their sense of youth and innocence just as the lost generation did.

Along with disillusionment with their current society, both generations felt a disconnect from traditional values. While the lost generation reversed gender roles, millennials are challenging gender roles, along with other controversial issues such as religion, abortion, and homosexuality. 33% of millennials believe it is a good thing for society to have mothers of young children working outside of the house, while 40% believe it does not make a difference, which is a higher acceptance rate than adults older than 30 (Kohut, Taylor and Keeter 124). Compared with their elders today, millennials are less likely to affiliate with any religious tradition. 25% of adults under age 30 are unaffiliated, describing themselves as “atheist,” “agnostic” or “nothing in particular.” Information from the General Social Surveys (GSS), which have been conducted regularly since 1972, reveal that not only are millennials more unaffiliated than their elders today, but are more unaffiliated than young people have been in recent decades (103). Around 52% of young adults believe that abortion should be legal in most cases, expressing slightly more permissive views than do adults aged 30 and older (104). This is a similar statistic to how many millennials believe that homosexuality should be accepted, at 50% (102).

Another similarity between the generations is the increased desire to travel. Both the lost generation and millennials seek traveling to increase their experiences and to escape their current situations. Among 18 to 24 year olds, experiencing a new culture and eating local foods were listed ahead of partying and shopping as common determining factors to travel (Lane). “Topdeck Travel, provider of group travel for 18-30 year olds, surveyed 31,000 people from 134 different countries: 88 percent of them traveled overseas between one and three times a year; 94 percent were between 18-30; 30 percent traveled solo; and the majority traveled in Europe, North America and Australia/New Zealand” (1). Along with wandering, the lost generation also used alcohol as a coping mechanism. Millennials have chosen a different substance, instead showing preference towards marijuana. 71% of the young adults are in favor of legalizing the drug, making them significantly more favorable than other generations (Geiger).

The most interesting similarity between the two generations, however, is their optimism. Despite the traumatizing circumstances that surrounded their adolescence and young adulthood, both generations rejected their labels, viewing them as negative. In The Sun Also Rises, the epitaph includes Stein’s famous quote “You are all a lost generation” (Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises), but Hemingway did not approve of Stein’s label, writing in his memoir “I thought of Miss Stein…and egotism and mental laziness versus discipline and I thought who is calling who a lost generation?...I will do my best to serve her and see she gets justice for the good work she had done as long as I can…but the hell with her lost-generation talk and all the dirty, easy labels.” (Hemingway, A Moveable Feast 35-36). Millennials also resist their label, with only 40% of adults ages 18 to 34 considering themselves part of the “Millennial generation” (“Most Millenials Resist the ‘Millennial’ Label”). This may be due to the association of millennials with laziness, selfishness, and other negative stereotypes.

One thing is clear, though, millennials are not cynical. While 68% of millennials believe that they are not earning enough money to live the life they want, 88% believe that one day they will (Kohut, Taylor and Keeter 40), a hopeful ideal considering the hardships millennials face with the changing global economy, student loans, and an uncertain job market. Neither the lost generation or millennials allowed themselves to be defeated, truly embodying Ecclesiastes’ quote which Hemingway included under Stein’s quote in the epitaph of The Sun Also Rises: “One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh; but the earth abideth forever…” (Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises).

References

Abrams, M. H. and Geoffrey Galt Harpham. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Eighth Edition. Boston: Michael Rosenberg, 2005. Print. 5 December 2016.

Advisors, The Council of Economic. “15 Economic Facts About Millennials.” 2014. December 5 2016.

Appignanesi, Richard, et al. Introducing Postmodernism. Duxford: Icon Books Ltd., 1999. Print.

Beach, Sylvia. Shakespeare and Company. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1956. Print.

Bertens, Hans. Literary Theory The Basics. London: Routledge, 2001. Print. 5 December 2016.

Domitrovic, Brian. “The Worst Economic Crisis Since When?” Forbes Magazine 3 February 2013. Web. 7 December 2016.

Earnest, Ernest. Expatriates and Patriots. Durham: Duke University Press, 1968. Print.

Elliot, T.S. The Waste Land. New York: Horace Liveright, 1922. Web. http://www.bartleby.com/201/.

Fitch, Noel Riley. Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983. Print.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. Tender Is the Night. New York: Scribner, 1934. Print.

—. The Great Gatsby. New York: Scribner, 1995. Print.

—. This Side of Paradise. New York : Scribner, 1920. Print.

Geiger, Abigail. “Support for marijuana legalization continues to rise.” Pew Internet & American Life Project 12 October 2016. Web. 5 December 2016. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/12/support-for-marijuana-legalization-continues-to-rise/.

Hemingway, Ernest. A Moveable Feast. New York: Scribner Classics, 1996. Print.

—. The Sun Also Rises. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926. Print.

Kohut, Andrew, et al. “Millennials Confident Connected Open To Change.” Pew Internet & American Life Project February 2010: 140. Web. 5 December 2016. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change.pdf.

Lane, Lea. “Are Millennial Travel Trends Shifting in 2016?” Forbes Magazine 15 January 2016: 2.

Mellow, James R. “The Stein Salon Was The First Museum of Modern Art.” New York Times 1 December 1968. Web. 7 December 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/05/03/specials/stein-salon.html.

“Most Millenials Resist the ‘Millennial’ Label.” Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, 2015. Web. 7 December 2016. http://www.people-press.org/2015/09/03/most-millennials-resist-the-millennial-label/.

Pound, Ezra. “And the days are not full enough.” n.d. Poetry.net. 7 December 2016. <http://www.poetry.net/poem/13194.>. Raphelson, Samantha. “Amid The Stereotypes, Some Facts About Millennials.” National Public Radio 18 November 2014. 5 December 2016. http://www.npr.org/2014/11/18/354196302/amid-the-stereotypes-some-facts-about-millennials.

Shmoop Editorial Team. The Waste Land. 11 November 2008. 7 December 2016. http://www.shmoop.com/the-waste-land/.

Stein, Joel. “Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation.” Time Magazine 9 May 2013. Website. 5 December 2016

Wagner-Martin, Linda, ed. A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. Print.

“World War I” History.com. 2009. 7 December 2016. http://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/world-war-i-history.