Oakland North End (ONE) Mile Project

ABSTRACT - Architecture is a tool that changes the way people live and physically interact with their environment, but sometimes it foregrounds formal aesthetic experimentation, forgetting to take into account the context and idiosyncrasies of a given place. Recently in Detroit, architecture has been criticized for this. ONE Mile is a project that combines architecture, urban design, and other creative disciplines to explore ways to positively impact challenging socio-economic scenarios. Launched in Detroit’s North End neighborhood, the project researches new methods and techniques that can help urban areas improve.

Objective - Delving into the past and present, as well as the future, in regards to community-led artist focused groups such as ONE Mile, we analyze how the project combats the exploitation of Detroit’s history through a grassroots approach.

Methods - Using the ONE Mile magazine, we strove to research the programming, as well as the narratives of residents from that area, including: artists, social activists, and business owners. In addition, newspaper articles documenting the history of the Detroit North End were collected and analyzed.

Results - Having documented the work of ONE Mile, as well as the rich history of the North End, the project can be considered a toolkit for other architects and urban planners who are working in similar urban conditions to have a positive impact socially and culturally.

**Oakland North End Mile Project **

Led by University of Michigan architecture professor, Anya Sirota, in partnership with her design studio, Akoaki, the Oakland North End (ONE) Mile project strives to create spaces for programs that revitalize areas through the use of pre-existing culture and available tools in such neighborhoods. ONE Mile researches new methods and techniques that can help improve such areas.

Historically, the Detroit North End has been home to a vibrant and flourishing community. It was part of the Highland Park area, where the Ford Motor Company Highland Park Plant was built in 1910. According to the National Parks Service, “Highland Park Ford Plant was the first automotive production facility in the world to implement a moving assembly line.” Due to this, a surplus of workers were needed in order to produce automobiles at a faster and more efficient pace. It was at the Ford Motor Company Highland Park Plant, where Henry Ford’s “$5 a day wage and 40 hour week was born,” (Henry Ford 150). This brought workers from across the United States and even the world flocking to Michigan for a chance to pursue the American dream. According to an interview conducted by Halima Cassels and Bashair Pasha for the ONE Mile magazine issue 2, local artist N’neka Jackson, who was born and raised in the North End neighborhood, states that “Highland Park was built because of the Model T factory that was there. It was actually built for the workers to have some place to live close to the factory. They had their own water treatment facility [and] their own college.”

The North End was also close to the Packard Plant, and the Russell Industrial Center, all automobile industrial sites which provided the area with an abundance of jobs (AHF). This made the North End one of the unique areas in Detroit where both blacks and immigrants were able to rise to middle class and own homes and businesses, which was not common at the time.

After its peak in the 1930’s the auto industry began to decline shortly thereafter, and at a quick pace. A mass exodus occurred with the economic decline after the collapse of the auto industry. This was caused by automation, and factories began to close, moving instead to new locations. As homes were abandoned, businesses owned by these homeowners also closed. The building of the Interstate Highway I-75 in 1959 also left many without homes. Occupying spaces that once held a significant amount of Detroit’s black history and business in areas such as Paradise Valley were I-75, Comerica Park and Ford Field. According to historian Thomas Sugrue “about one-third of the Gratiot-area’s families eventually moved to public housing, but 35 percent of the families in the area could not be traced.” (Sugrue 10).

Currently, Detroit is home to a dichotomous array of architectural and development practices. One of the major players in Detroit’s landscape is Dan Gilbert. A Detroit born businessman and Quicken Loans founder, “Gilbert has invested heavily in the city of Detroit, touting plans for a vibrant technology and entertainment hub. He has acquired some 95 properties since early 2011, including a $600 million purchase of Greektown Casino and Hotel” (Forbes). In an article written by journalist Anna Clark for Columbia Journalism Review, Clark says that although Gilbert has notably been involved in a lot of the efforts to revitalize Detroit, there hasn’t been enough local research and analysis of his efforts to make a decision on whether his efforts are good or bad. “Despite their outsized presence, today’s development moguls don’t directly support major civic institutions like libraries and universities the way earlier industrial titans like Carnegie and Mellon did. Pushing the point a little further might clarify the ways in which Gilbert’s Detroit strategy will—or won’t—sustain the city’s public realm.”

In the article “North End, Detroit Neighborhood East Of New Center, Is Focus Of Organic And New Development” published in the Huffington Post, Dennis Archambault states that Detroit is “emerging as home to a diverse mix of race, culture, and entrepreneurial interests, as well as space where art and agriculture create a sense of place”.

Resident led projects, like ONE Mile, look to use architecture and design to fulfill this need to create a sense of place. The project’s website lists their multitude of goals: “We host events, exhibits, workshops, and performances. We create public spaces and experimental environments. We design tools for broadcast and dissemination. And we continue to build a network of people interested in the sustained collective vibrancy of the North End.”

After receiving the Knight Arts Challenge grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Sirota set out to further explore the Oakland Avenue neighborhood and its rich history. After holding a town meeting type public dialogue in the neighborhood, in partnership with the Oakland Avenue Artists Coalition, a team of people began to form. Led by Sirota, along with her design studio partner, Jean-Louis Farges, the ONE Mile team consists of a network of socially active Detroiters, including artist and activist Halima Cassels, and cultural organizer Bryce Detroit, along with U of M graduate architecture students and volunteers.

The team’s first big project in the neighborhood soon became a local icon of the North End. Dubbed “the mothership,” a gold and white spaceship, the astral invention is a portable DJ booth that is now used by local artists at festivals and concerts (Sirota). Created as a symbol of the birth of funk music, a movement that first began on Oakland Avenue, the mothership is a replica of the spaceship used by Detroit’s own Parliament-Funkadelic, an acclaimed musical group that was largely responsible for the creation of funk. The original spaceship used as a prop on stage by P-Funk is now housed in the Smithsonian Institute.

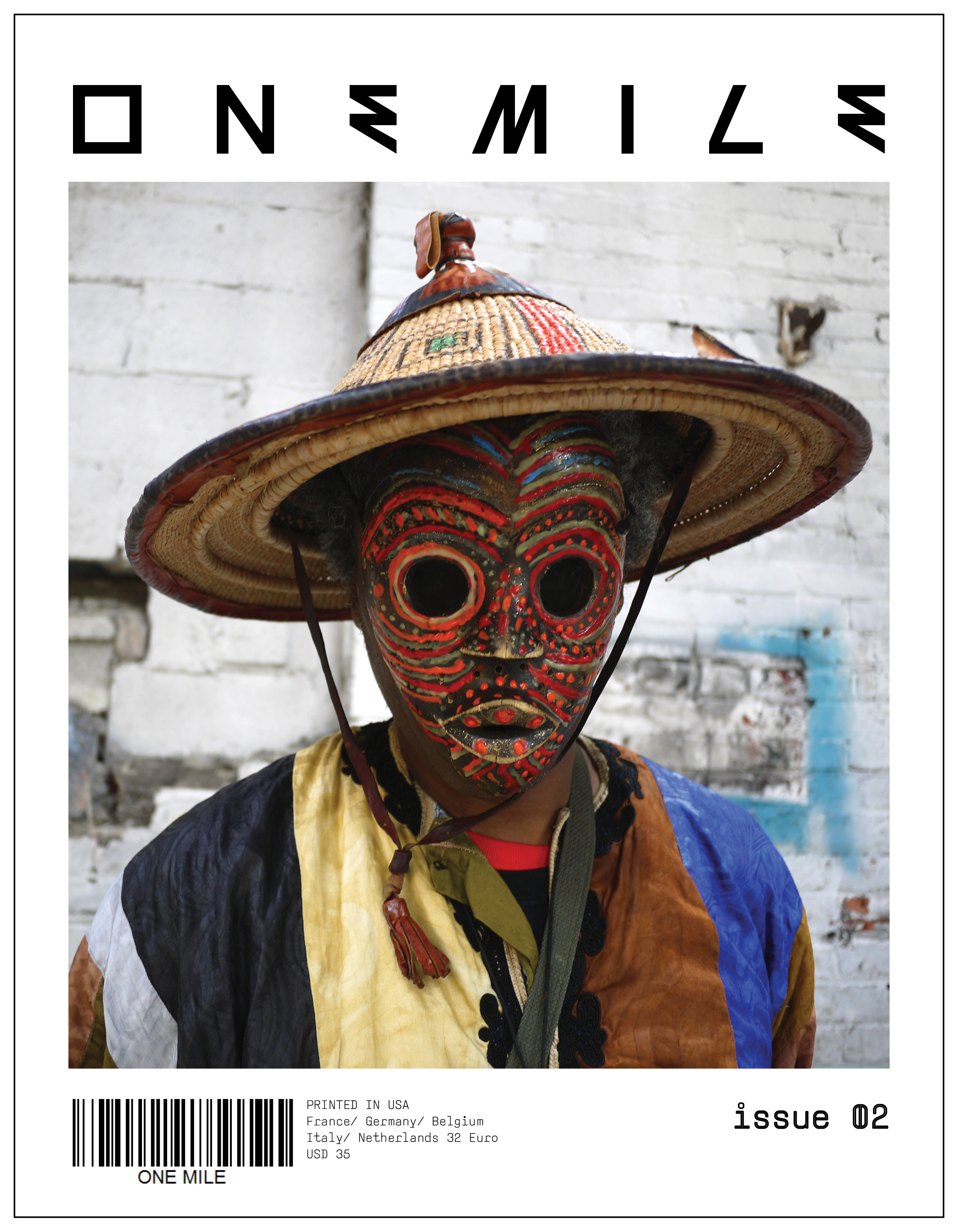

In the fall of 2014, ONE Mile launched their project by holding a concert, headlined by P-Funk, using the mothership. Since then, ONE Mile publishes a magazine biennially, chronicling their work and a variety of artists in the North End neighborhood. Currently, there have been two of these magazines published.

In the summer of 2016, the ONE Mile team was working on compiling the content for the second issue of the magazine. The project included interviews from Detroit artists and residents. One of these artists is N’neka Jackson, is a jewelry maker whose “custom creations are both regal and empowering, bringing together mythical flash with whimsical futurism,” according to the magazine. She creates traditional jewelry like necklaces and bracelets, and also makes wings and regal crowns. Jackson’s pieces have been worn on runways internationally.

The project combines architecture and design in nontraditional ways, using the disciplines in a new, grass-roots oriented way. In an interview with online magazine Model D, Sirota addresses the concern of outsider projects working in Detroit not always understanding the rich culture and history of certain neighborhoods, while taking into account the challenges Detroit residents face. Architecture, design and other art-based programs, especially, have been criticized for exploiting Detroit’s history of decline and struggle for financial profits. “There are lots of people who use Detroit as a backdrop for arts practices and design practices – corporations especially do a very good job of it, lending themselves authenticity by using Detroit as a scenography to brand their own identity or their own product,” Sirota says. “The way we walked into this project was to assume that we wouldn’t bring any programming to any context, we would support the programming that was already happening there.”

This mindset is what makes ONE Mile unique from developers such as Mike Ilitch and businessman Dan Gilbert. Using tools that are not readily available to residents in the North End neighborhood, ONE Mile strives to create the visions and ideas that these residents have. The ONE Mile project continues to exist with funding from grants including the Knight Arts Foundation, ArtPlace America and Creative Many’s Resonant Detroit Program.

Research from the ONE Mile project can eventually be considered a blueprint for other architects and urban planners who are working in similar urban conditions to have a positive social impact on people’s lives.

Works Cited

AHF. “Resurrecting the Ghostly Three.” Resurrecting the Ghostly Three: Automotive Hall of Fame. Automotive Hall of Fame, 29 Oct. 2015.

Archambault, Dennis. “North End, Detroit Neighborhood East Of New Center, Is Focus of Organic And New Development.” Huffington Post 26 Feb. 2013: n. pag. Print.

Clark, Anna. “Detroit’s Dan Gilbert and the ‘savior complex’”. Columbia Journalism Review 18 Aug 2014. Web.

“Highland Park Henry Ford 150.” Henry Ford 150. N.p., n.d. Web.

National Park Service. “National Register Information System”. National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. NPS. “Highland Park Ford Plant.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d. Web.

Sirota, Anya. ONE Mile magazine. 18 July 2016. ONE Mile Web. 4 December 2016.

Sugrue, Thomas. Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton University Press, 2005), p. 10 “#120 Daniel Gilbert.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, n.d. Web.