Does Nonverbal Communication Create Intimacy Between the Leader and the Audience?

Abstract - Nonverbal communication is displaying of emotions, feelings, and messages through actions and expressions rather than words. Research indicates that 93 percent of human communication is done using body language (kinesics). The objective of this paper is to understand how positive hand gestures have a greater effect on the audience and less to no hand gestures will have less effect on the audience. The paper uses different types of hand gestures during the 2016 presidential debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. This comparative study identifies if the hand gestures elicited positive or negative intimacy with the audience. The study chose presidential debates to understand the importance of nonverbal communication in political communication. The study categorizes the different gestures as community hands, humility hands, steepling, precise, power and slice for all the three debates based on research by Talley and Temple (2015). The coder used categorization to identify positive and negative impact on the audience. To measure the intimacy, debate reactions and statistics captured by news channels were used to validate the hypothesis- more positive gestures makes the leader appear more favorable to the audience. This analysis proves that nonverbal communication plays a significant role in the power of speech. Though gestures may appear spontaneous they are used strategically in front on the target audience. Televised political debates have clearly identified the importance of kinesics/nonverbal communication along with verbal communication. The paper identifies further research in understanding the impact that women’s and men’s nonverbal forms of communication have on voters’ evaluations of political figures. Measuring audience intimacy referenced the nonverbal intimacy observer report by James McCroskey to further validate the importance of nonverbal communication in speech.

Everyone has wondered at some point if some politicians are born with the talent of convincing a crowd of people using only the power of speech. The ability to have a crowd’s approval is not an easy goal to achieve, and it requires more than just words. In fact, 93% of human communication is non-verbal. Communication experts generally agree that when two people are engaged in a face to face conversation, only a small fraction of the total message they share is contained in the words they use (Paul Preston, 2005). Politicians today are aware of the importance of their image and appearance. Their gestures may seem spontaneous, but they are in fact calculated and used in a strategic manner in front of the targeted audience. Research by Choi et al. (2009) noted that observers are capable of perceiving and interpreting nonverbal communication as a way to interpret the perception as either attractive or distancing. This research showed that the attraction between a leader and his or her followers is determined by the nonverbal interpretation of the meaning of these nonverbal messages (Choi et al., 2009). Emotions, or nonverbal communication, are leaked through facial expressions or body gestures. Developing and understanding the nuances of nonverbal behavior, particularly specific hand gestures can give the candidate an advantage against his or her opponent (Talley and Temple, 2013). Richmond et al. (2008), posited a corollary to this work by noting that more nonverbal immediacy a person uses, the more other people will evaluate in a positive manner and prefer to be around him or her. It is also true that the less nonverbal immediacy a leader uses, the exact opposite will happen.

This study attempts to go more in depth with that research by looking on how exactly do leaders create that intimacy with the audience. A similar study was done by Linda Talley and Samuel Temple (2013), which found that there is a difference among gesture groups and that the difference between the gestures will be measured by immediacy as perceived by the audience. In order to study this, I watched the three presidential debates between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton during the 2016 presidential election to test the following hypotheses:

H1: The more a candidate uses positive hand gestures, the greater their effect will be on the audience.

H2: The candidate with less to no hand gestures will have less effect on the audience.

The experiment:

In this experiment, I watched three two-hour-long videos of the presidential debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. I recorded every time they would make a hand gesture and kept track during the whole debate. Some of the gestures include:

Community hands: the position of the hands show the palm face up or vertical to the ground.

Humility hands: hands are clasped in front of the person at waist level.

Steepling hands: hands form a steeple with fingertips touching.

Precise hands: index and thumb touching like as if holding a pen.

Power hands: hand closed forming a fist.

Slice hands: palm is vertical making a rigid slice movement

Method:

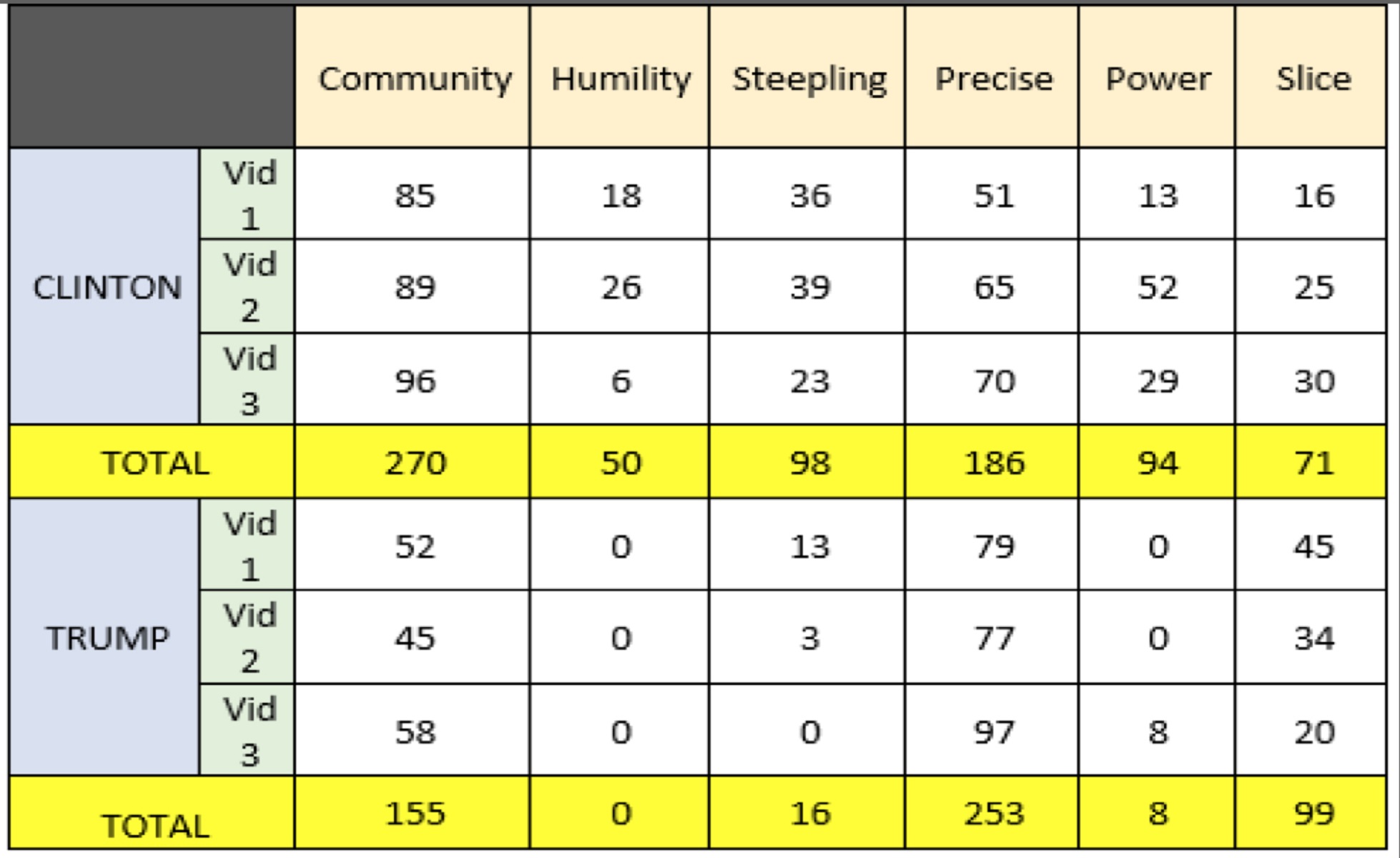

For each time the candidate would make a gesture I would record it in a chart. Sometimes candidates maintain one gesture for a longer time, but I would still count it as one time until they changed it to another gesture. The results were the following: Clinton has a diverse chart. She uses all the hand gestures with a domination of community and precise hands. Trump used the precise hand the most. He never used humility hands and seems to use more powerful hands such as slice movement.

Findings:

According to Statistica.com, 62% of public opinion agreed that Hillary won the first debate; 57% agreed that Hillary won the second debate; and 52% agreed that she won the third debate.

Reuters asked adults who are likely voters who did the better job in the last debate. 55% said that Hillary did a better job. When asked about their view about Hillary Clinton, 34% said that their view changed to more positive after the debate. Only 19% think that their view changed positively towards Donald Trump.

Discussion:

More factors probably contribute to the influence that leaders have on their audience, one of them is the expectations the audience have for them.

According to Judee K. Burgoon & Jerold L. Hale, nonverbal expectancy violations theory holds that positive violations produce more favorable communication outcomes than conformity to expectations, while negative violations produce less favorable ones, and that reward characteristics of the communicator mediate the interpretation and evaluation of violations. Which means that the public expects certain behavior from a candidate who will rule the country: (Charisma, wisdom, intelligence…) and if that expectation is violated negatively, chances are the public is not going to vote for that candidate and vote for the candidate who met their expectations or violate them in a positive way ( more charisma, wisdom and intelligence than expected.) Non-immediacy violations produced lower credibility ratings than high immediacy or conformity to expectations for both friends and strangers. Non-immediacy was interpreted as communicating detachment, non-intimacy, dissimilarity and more dominance than normal immediacy, while high immediacy expressed the most intimacy, similarity, involvement and dominance. Implications for the role of ambiguity in violations are discussed.

In future studies, I would like to look into how the gender, race or age of a leader affects the audience they are communicating with. Nonverbal communication can be different between the genders and that would be an interesting topic to research as well.

Works Cited

Dumitrescu, D. (2016). Nonverbal Communication in Politics: A Review of Research

Developments, 2005-2015. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(14), 1656–1675. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764216678280.

Gong, Zijian Harrison, and Erik P. Bucy. “When Style Obscures Substance: Visual Attention to

Display Appropriateness in the 2012 Presidential Debates.” Communication Monographs, vol. 83, no. 3, 2016, pp. 349–372., doi:10.1080/03637751.2015.1119868.

Ihcker. YouTube, YouTube, 11 Apr. 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=7DHcn7KXMZ0.

Patterson, Miles L., et al. “Verbal and Nonverbal Modality Effects on Impressions of Political Candidates: Analysis from the 1984 Presidential Debates.” Communication Monographs, vol. 59, no. 3, 1992, pp. 231–242.

Preston, Paul. “Nonverbal Communication: Do You Really Say What You Mean?” Journal of Healthcare Management, vol. 50, no. 2, 2005, pp. 83–86.

Streeck, Jürgen. “Gesture in Political Communication: A Case Study of the Democratic Presidential Candidates During the 2004 Primary Campaign.” Research on Language & Social Interaction, vol. 41, no. 2, Sept. 2008, pp. 154–186.