October

“You cheating bastard”, I heard my mother yell as I made my way up the sidewalk to our trailer, some single wide mobile home that managed to make it out of the 80’s. It was beginning to crumble around us as our makeshift family did the same. I pause outside of the front door not knowing what conflict I would be walking into.

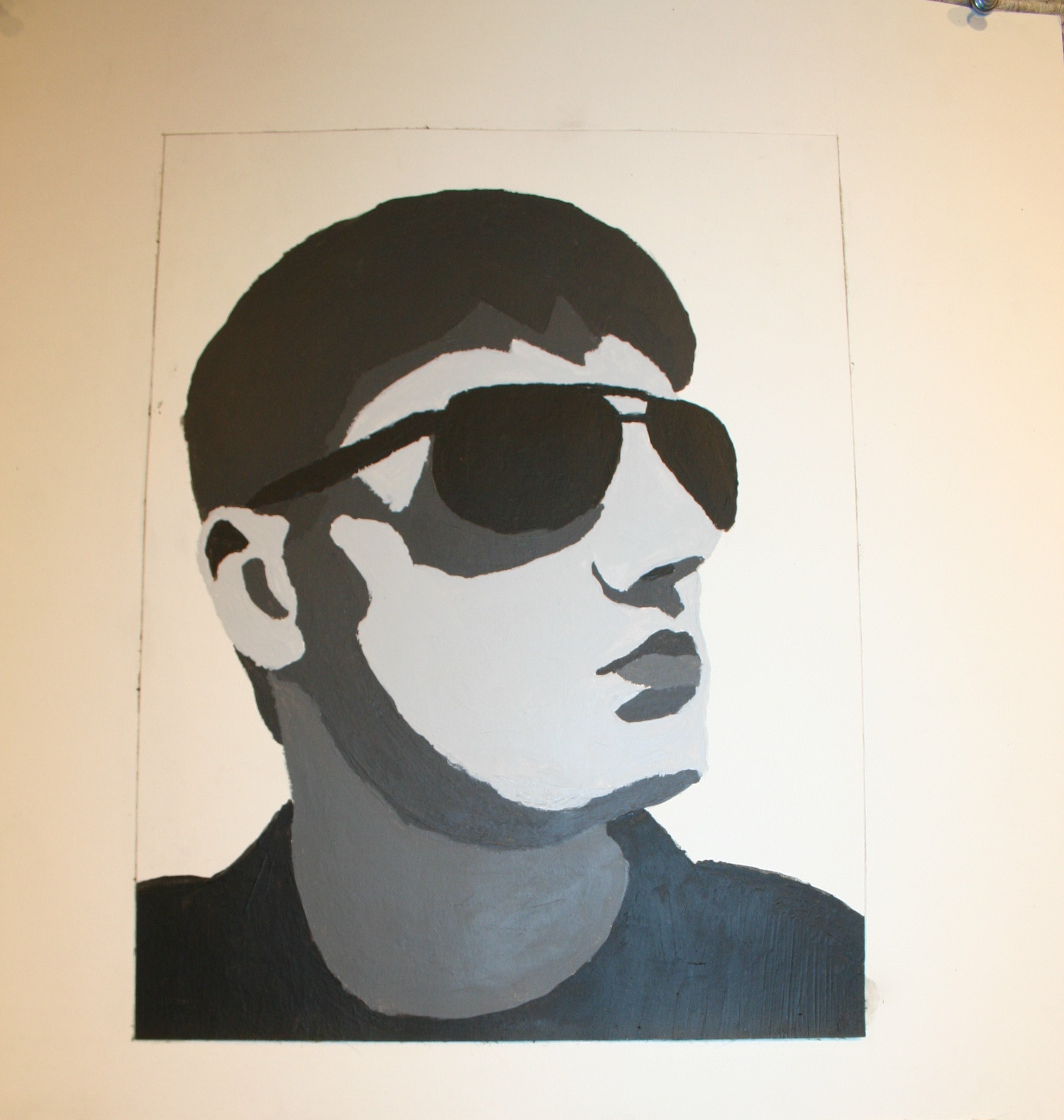

My mother had met him eight years before, while frequenting some local motorcycle club in the hopes of finding a free drink and a new companion. She found what she wanted, a biker by the name of EZ, yet she introduced my sister and I to him under the name Brian. He was taller than anyone I had ever known, with sleeves of tattoos that were starting to fade in their age. I was young then and didn’t really know what red flags to look for, after all how much can a 9- year-old know about how the world really works and why adults do the things they do. Anyways, within three months of their first meeting, we moved in with him. Some 2-bedroom apartment on the east side of Wayne just another suburban ghetto, not as bad as Shacktown or Norwayne, yet it’s not somewhere to revisit. Columbus Apartments was the name of the place, looking back it seems funny. I’d discover a whole new world and what it would take for me to survive it, or at least what I would need to do to remain sane while in it.

So, we move in with this stranger. My sister and I share the larger room and stay there most of the time, entertaining ourselves with our own toys, occasionally being forced to play with the kids that lived in the flat above us, never minding the fact that they ate their meals on the kitchen floor, using milk crates as makeshift tables. What does a child know about what’s right and wrong? Regardless we would play around in the parking lot. Avoiding hitting the cars with a ball like they were the plague, away from the adults.

We would come inside and notice a strange scent in the air. Our mother told us it was nothing, and I wish it truly was. Every so often you could catch it drifting out from under the door of their room, into the hallway, to us. My mother would act oblivious. Sidestepping questions and changing the subject in record time. I still don’t know if it was to protect us or if she just did that because lying was easier. A year of that went by until that door swung open and I could see him sitting there on his bed with some bit of crumpled aluminum foil being held to his mouth, and a lighter underneath it. I was ten then. And my mother reacted strongly.

Within 3 hours we had packed up everything we had owned and moved into my grandmother’s basement. I continued to ask questions that were never answered.

I’d say something like, “Is brain coming with us?”

Mom would give a nervous look, clearly agitated by the question.

That was in October, by February she was back with him, and we were living in a nice new trailer in the middle of Woodhaven, a majority of which was upper middle class. We could see their condos on right across the great divide, Van Hom. A road that ran east to west. On the north we had the lovely neighborhood, Flower Creek. On the south side there was us. Our community provided the Jones’ with whatever release they needed. Easy drugs and easy women for a reasonable price. I was 11.

We moved in right before I had started the 6th grade and oddly enough nothing happened that year. There was some casual dance that the school held that was designed to mimic the idea of a prom in the middle of winter and in my desperation, I had timidly asked my mother if I could go.

“Ask Brian to lend you a tie”, she said with cigarette perched in the comer of her mouth.

So, I did. He opened up a small drawer in his dresser and asked

“So ya got a hot date?” I had laughed and said no.

“Well here. Try this on,” Handing me a pale blue tie with specks of gray. “Of course, you don’t know how to tie it, stand up straight” and that is what I did as he tied it in a few easy steps. “Looks sharp kiddo.”

In a year, tensions to grow, addictions spring up, and Brian goes on a bender with a few other members of his motorcycle club. We can’t make the payments on this new home, so we move to another, just around the block. Pressure builds in that crisp autumn. Some dinners are smaller than others. Some clothes just don’t fit right. I start being able to feel these desperate tones the people around me send out. Like signals projecting outwards, but the reception still isn’t great so a lot of it just goes over my head. A woman across the street becomes friends with my mother and they trade pills when the mood suits them. They would often meet up by the mailboxes because it seemed perfectly reasonable to run into your neighbor while picking up your mail.

“You got any more zannies?” the neighbor would ask.

My mother would reply, “Well, let me get home and do some counting, I need to go and get a new script.”

The neighbor said, “Well, let me know, I need em.”

Meanwhile I was shifting around in the back seat, trying to act as if I hadn’t been eavesdropping on them iron out the details of their little drug deal.

Brian goes back to doing what we knew him for. Tensions rise, we have two bathrooms on either side of the home. One becomes a grow room. My sister and I get told that we can never use that bathroom again and to never mention it or ask questions about it. “It’s how we get to live here”, our mother said. That’s all we knew until I learned what signals meant what, what pot was, and how much they could make off a plant.

I knew what Brian was holding, yet that make-shift aluminum foil pipe was raised up to his lips was for a reason more devious than what I originally thought. Addiction became a known thing. That constant struggle that could be seen in everyday life now had a name. We could highlight the reasons why certain questions could start a fight and what certain verbal tones really meant. It’s funny how you only learn that certain things are a problem when they are clearly labeled for you.

So, I gained a 6th sense, whispering to me these ideas of when his addiction would likely flare up. Noticing the slight movements that suggest agitation, and how easy it was to push the wrong button. I learned how to feel it. Like the moon controlling the rise and fall of tides and how that drug that had so much of my own life riding on those shifting waters. Whether I liked it or not, this man was my father figure. I would go to him for advice and share how my day went with him, who I had now known for years. When that tide of addiction came in, it would drown us. To know that what we had could suddenly come to an end. And that’s how it went. He would enjoy his drug of choice and we would move down the street, some early October day.

It never made much sense why we would only move around in the same neighborhood, rather than try to get out fully. The only thing I can think of is that it was cheaper, and it was for obvious reasons. It was horrifically small and outdated. 8-foot ceilings, two bedrooms and a peculiar fungal growth that sprouted in my doorway. They didn’t believe me until they finally came to check on it. A mushroom with a thin grey stem supporting a small bell with a crown of a darker shade of red. We tore up the floor to find some type of black mold had spread like wildfire. The whole place should have been condemned. Yet a 14-year-old doesn’t have too many options in the way of alternative housing. My mother had always stayed silent unless she saw something as a direct attack against herself. So, one day when she found a used crackpipe, as well as a used condom, the evidence pointed to our next-door neighbor.

“You cheating bastard,” she yelled with all her might, loud enough for me to hear from outside of our home, I knew that my senses were tingling for a good reason earlier that morning, as I walked to school. October always brought about the same tension.

As I stepped in through the front door, a knot made its way into my chest. Brian sat in his chair watching TV as if my mother wasn’t even there. Yet she carried on. “How could you do this to me?” She beckoned. I too felt the need to ignore her, and walked to my room. And as soon as I close that bedroom door behind me, I threw down my bag and started to pack. I know how things go by now. By the end of the night, we would be at my grandmother’s. We slept on musty couches while the adults decide the best course of action in the next room. We would skip class and pack up everything we owned. I didn’t think much of it at the time. There is a certain numbness that comes with a repetitive stressor.

“I’ll see you next Wednesday”, was the last thing I had ever said to him, because this had happened so often I thought that we would be back by early next week. And the last thing he ever said to me? “I don’t know about this time bud, I fucked up.”

Seven months later Brian died to a mixture called a “Hot Pack”, a combination of cocaine to get high, and then heroin to come back down to earth. It was a known way to help addicts sleep after a bender. The only problem is that he never woke up. In some ways that served as closure. Never again would I need to wonder if I had just passed him on the street. Of course, I would rather see him alive and well, but that kind of wishful thinking just leads to unnecessary grief at this point. October still brings a feeling of unease regardless of what I tell myself.